Rational Voter Theory

Welcome to a deep dive into the intriguing world of Rational Voter Theory, a cornerstone concept in political science and behavioral economics. This theory sheds light on the seemingly complex decisions made by voters, offering a nuanced understanding of the political landscape. As we explore this topic, we'll uncover the factors that influence voter behavior and the role of rationality in political decision-making.

The study of voter behavior is a critical component in understanding the dynamics of modern democracies. It provides insights into how citizens make choices that shape the political trajectory of their nations. Rational Voter Theory, in particular, proposes an interesting perspective, suggesting that voters make decisions based on a careful analysis of information and their own self-interest.

Unraveling Rational Voter Theory

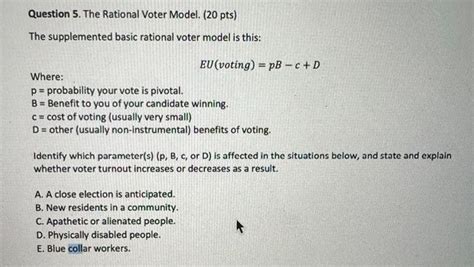

At its core, Rational Voter Theory posits that individuals make voting decisions rationally, considering their personal beliefs, values, and the available information. This theory challenges the notion of voters as passive or uninformed participants in the democratic process, instead portraying them as active agents who weigh their options strategically.

The key tenets of this theory include the idea that voters:

- Seek information about candidates and policies.

- Evaluate this information based on their personal preferences.

- Make choices that they believe will benefit them or align with their values.

This approach to voter behavior stands in contrast to other theories that suggest voters are swayed by emotional appeals, personal biases, or simple heuristics.

Information Processing in Voter Decisions

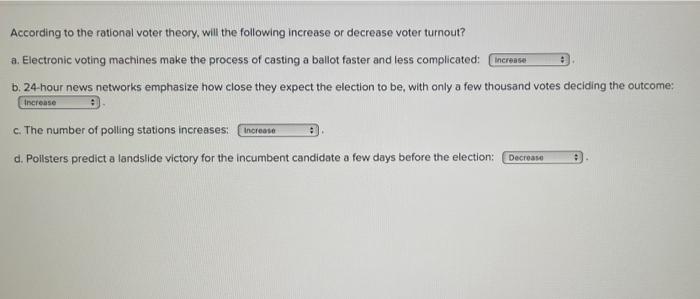

A crucial aspect of Rational Voter Theory is the emphasis on information processing. Voters are assumed to have access to a variety of sources, including media outlets, political campaigns, and personal networks, from which they gather data about candidates and issues.

Imagine a hypothetical scenario where a voter, let's call them "Voter A," is deciding between two candidates in an upcoming election. Voter A might consider the candidates' positions on key issues, their past records, and any promises they've made during the campaign. They might also factor in personal experiences or values that align with one candidate more than the other.

| Candidate | Position on Key Issue X | Past Record |

|---|---|---|

| Candidate 1 | Supports a progressive approach | Mixed record, but recent successes |

| Candidate 2 | Opposes progressive measures | Consistent track record |

Voter A, armed with this information, would then make a decision based on their personal beliefs and the perceived benefits of each candidate's platform.

The Role of Self-Interest

Another critical component of Rational Voter Theory is the role of self-interest. Voters, according to this theory, are driven by their own best interests when making political decisions. This doesn’t necessarily mean that voters are selfish, but rather that they prioritize outcomes that they perceive as beneficial to themselves or their communities.

For instance, a voter might consider the impact of a candidate's policies on their personal finances, the stability of their neighborhood, or the opportunities available to their children. These considerations are often deeply personal and can vary widely across the electorate.

Challenges and Criticisms of Rational Voter Theory

While Rational Voter Theory offers a compelling framework for understanding voter behavior, it’s not without its critics and limitations.

The Complexity of Real-World Decisions

One of the primary challenges with this theory is the assumption that voters have the time, resources, and cognitive capacity to process complex political information. In reality, many voters face time constraints, limited access to diverse information sources, and varying levels of political sophistication.

Furthermore, the theory often struggles to account for the emotional and social factors that can influence voting decisions. For instance, voters might be swayed by a candidate's charisma or the social pressure to align with a particular political group.

Empirical Evidence and Alternative Theories

Empirical studies on voter behavior have yielded mixed results when it comes to supporting Rational Voter Theory. While some research suggests that voters do exhibit rational behavior, especially in well-informed electorates, other studies highlight the role of non-rational factors, such as ideological biases or simple heuristics.

Alternative theories, like the Affective Voting Theory, propose that emotions and affective responses play a more significant role in voting decisions than previously thought. These theories suggest that voters may be more swayed by their emotional reactions to candidates or issues than by rational analysis.

Implications for Democracy and Policy Making

The insights provided by Rational Voter Theory have significant implications for how we understand and engage with democratic processes. For policymakers, understanding that voters make decisions based on rational assessments of information can inform strategies for communicating policies and engaging with the electorate.

For instance, policymakers might prioritize clear and accessible communication of policy proposals, ensuring that voters have the information they need to make informed decisions. They might also consider the diverse information sources and biases that voters rely on, tailoring their messages to resonate with different segments of the electorate.

Enhancing Voter Education and Engagement

Rational Voter Theory also underscores the importance of voter education and engagement. By empowering voters with the skills and knowledge to evaluate political information critically, we can foster a more informed and active electorate. This, in turn, can lead to better democratic outcomes and more effective governance.

Initiatives focused on media literacy, civic education, and voter outreach can play a crucial role in enhancing voter engagement. By providing voters with the tools to navigate the complex political landscape, we can encourage more thoughtful and rational decision-making.

Conclusion: A Nuanced Perspective on Voter Behavior

Rational Voter Theory offers a fascinating lens through which to understand the intricate world of voter behavior. While it provides valuable insights into the decision-making processes of voters, it’s important to recognize its limitations and the role of other factors, such as emotions, social influences, and personal biases.

As we continue to explore and understand the complexities of voter behavior, theories like Rational Voter Theory serve as valuable building blocks, offering insights that can inform and improve our democratic processes. By recognizing the rationality of voters and the factors that influence their decisions, we can work towards a more inclusive, informed, and engaged democracy.

How does Rational Voter Theory compare to other theories of voter behavior?

+

Rational Voter Theory differs from other theories, such as Affective Voting Theory, by emphasizing the role of rational information processing and self-interest in voting decisions. While Affective Voting Theory highlights the influence of emotions and affective responses, Rational Voter Theory focuses on the cognitive processing of political information.

What are some of the criticisms of Rational Voter Theory?

+

Criticisms of Rational Voter Theory often center around the assumption that voters have the time, resources, and cognitive capacity to process complex political information. Additionally, the theory may struggle to account for the role of emotions, social influences, and personal biases in voting decisions.

How can policymakers use insights from Rational Voter Theory to engage with voters effectively?

+

Policymakers can leverage insights from Rational Voter Theory by prioritizing clear and accessible communication of policy proposals. They should consider the diverse information sources and biases that voters rely on, tailoring their messages to resonate with different segments of the electorate. By understanding that voters make decisions based on rational assessments of information, policymakers can craft more effective strategies for engaging with the electorate.